Approach, my soul, the mercy seat

Five Motivations to Pray

Prepare Your Public Prayers: Helpful Advice from D. A. Carson

D. A. Carson's helpful advice for people who lead in public prayer:

"If you are in any form of spiritual leadership, work at your public prayers. It does not matter whether the form of spiritual leadership you exercise is the teaching of a Sunday school class, pastoral ministry, small-group evangelism, or anything else: if at any point you pray in public as a leader, then work at your public prayers.

John Owen on the Work of the Spirit in Prayer

- "Freedom of speech" is the ability of the heart to "express all its concerns unto God as a child unto its father."

- And by "confidence of acceptance" Owen means not the assurance that we'll get every single thing we ask for, but rather the "holy persuasion that God is well pleased" with our prayers and accepts us when we come to his throne.

- He inclines our wills and stirs our affections towards God

- He gives us earnestness in seeking God

- He gives us delight in God as our Father and boldness to approach his throne of grace

- He keeps us focused on Christ as the sole means of approaching God

- Am I relying on the Spirit to incline my heart to God?

- Am I trusting in the Spirit to make me earnest in prayer?

- Am I approaching God's gracious throne with the free and delightful boldness of an accepted child?

- Am I trusting in Christ alone to give me access to God?

Why God Gave Us the Psalms

When our son Matthew was just two or three years old, he informed Holly and me that he couldn’t skate. “I can’t skate. I can’t skate,” he said. We didn’t really get it, until we realized that he was sick, but didn’t know how to tell us. He needed words and couldn’t find the right words to say, so he quoted what he knew best: Winnie the Pooh!

We all sometimes struggle to find words to express our feelings. That’s why God gave us the Psalms.

An Anatomy of All the Parts of the Soul

The sixteenth century Reformer John Calvin called Psalms “the Anatomy of all the parts of the Soul” and observed that

There is not an emotion of which any one can be conscious that is not here represented as in a mirror. Or rather, the Holy Spirit has here drawn . . . all the griefs, sorrows, fears, doubts, hopes, cares, perplexities, in short, all the distracting emotions with which the minds of men are wont to be agitated.

Or, as someone else noted, while the rest of the Scripture speaks to us, the Psalms speak for us. The Psalms provide us with a rich vocabulary for speaking to God about our souls.

When we long to worship, we have psalms of thanksgiving and praise. When we are sad and discouraged, can pray the psalms of lament. The psalms give voice to our anxieties and fears, and show us how to cast our cares on the Lord and renew our trust in him. Even feelings of anger and bitterness find expression in the infamous imprecatory psalms, which function something like poetic screams of pain, lyrical outbursts of anger and rage. (The point being honesty with your anger before God, not venting your anger at others!)

The Drama of Redemption in the Theater of the Soul

Some of the Psalms are downright bleak. Take Psalm 88, which contends for one of the most hopeless passages in all of Holy Scripture. But even those psalms are helpful, for they show us that we are not alone. Saints and sinners from long ago also tread through the valley of death’s dark shadow. You’re not the first person to feel enveloped in the hopeless fog of despair.

But more than that, the psalms, when read as a whole, depict the drama of redemption in the theater of the soul. Some biblical scholars have observed three cycles in the psalms: the cycles of orientation, disorientation, and reorientation.

- Psalms of orientation point us to the kind of relationship with God we were created for, a relationship marked by confidence and trust; delight and obedience; worship, joy, and satisfaction.

- The psalms of disorientation show us human beings in their fallen state. Anxiety, fear, shame, guilt, depression, anger, doubt, despair – the whole kaleidoscope of toxic human emotions find a place in the Psalms.

- But the psalms of reorientation portray reconciliation and redemption in prayers of repentance (the famous penitential psalms), songs of thanksgiving, and hymns of praise that exalt God for his saving deeds, sometimes pointing forward to Jesus, the Messianic Lord and Davidic King who will fulfill God’s promises, establish God’s kingdom, and make all things new.

These cycles mirror the basic story line of Scripture: creation, fall, and redemption. We were created to worship God. As the old catechism says, “Man’s chief end is to glorify God and enjoy him forever.” But the fall and personal sin leave us disoriented. Our lives, more often than not, are fraught with anxiety, shame, guilt, and fear. But when we encounter our redeeming God in the midst of those distressing situations and emotions, we respond with renewed penitence, worship, thanksgiving, hope, and praise.

The Psalms as Tools for Prayer

Just learning these basic cycles will help us understand how the various psalms can function in our lives. To echo Eugene Peterson, the psalms are tools for prayer.

Tools help us get a job done, whether it is repairing a broken faucet, building a new deck, changing an alternator in a vehicle, or hacking our way through a forest. If you don’t have the right tools, then you’ll have much more difficulty accomplishing the task.

Have you ever tried to use a Phillips screwdriver when you really needed a flathead? Frustrating experience. But that’s not because of a defect in the Phillips. You just chose the wrong tool for the task at hand. One of most important things we can learn in walking with God is how to use Scripture as he intended. All Scripture is inspired by God, but not all Scripture is suited to every state of heart. There is a God-given variety in the Spirit-breathed word – a variety that befits the complexities of the human condition. Sometimes we need comfort, sometimes instruction, while at other times we need prayers of confession and the assurance of God’s grace and pardon.

For example, when I’m struggling with anxious thoughts, I am strengthened by psalms that point to God as my rock, my refuge, my shepherd, my sovereign king (e.g. 23, 27, 34, 44, 62, 142). When I’m beset with temptations, I need the wisdom of psalms that direct my steps in the ways of God’s righteous statues (e.g. 1, 19, 25, 37, 119). But when I’ve blown it and feel overwhelmed with guilt, I need psalms that help me hope in God’s mercy and unfailing love (e.g. 32, 51, 103, 130). And at other times, I just need to tell God how desperately I desire him, or how much I love him, or how I long to praise him (e.g. 63, 84, 116, 146-150).

Finding and praying the psalms that best fit your varied states of heart will, over time, transform your spiritual experience.

Don’t Wait Till You’re in Trouble, Start Now

I hope that people who are currently struggling and suffering will read this and immediately take refuge in the psalms. But for those who aren’t presently in dire straits, let me say this. Don’t wait till you’re in trouble to read and pray the psalms. Start now.

Build for yourself a vocabulary for prayer. Get well acquainted with the anatomy of your own soul. Immerse yourself deeply in the drama of redemption that plays out in the theater of the human heart – in the theater of your heart. Familiarize yourself with these divinely given tools. Learn to use them well.

Use God’s word to talk with God.

This post was written for Christianity.com.

Rescue Your Prayer Life

- First, we mean that there is only one God. "Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one" (Deuteronomy 6:4).

- Second, this one God exists in three distinct persons, or personalities: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

- Third, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are each fully, equally, and eternally God.

- We have "access…to the Father."

- But that access to the Father is "through him" - Jesus Christ, God's Son, who reconciles us to the Father (see Ephesians 2:11).

- But notice further that our access to God is "in one Spirit". This means that our prayers are enabled and empowered by the Spirit.

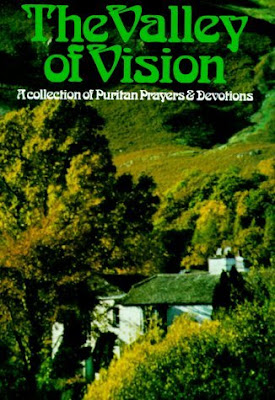

Purification

Deliver me from attachment to things unclean, from wrong associations, from the predominance of evil passions, from the sugar of sin as well as its gap; that with self-loathing, deep contrition, earnest heart searching I may come to Thee, cast myself on Thee, trust in Thee, cry to Thee, be delivered by Thee.

O God, the Eternal All, help me to know that all things are shadows, but Thou art substance, all things are quicksands, but Thou art mountain, all things are shifting, but Thou art anchor, all things are ignorance, but Thou art wisdom.

If my life is to be a crucible amid burning heat, so be it, but do Thou sit at the furnace mouth to watch the ore that nothing be lost. If I sin wilfully, grievously, tormentedly, in grace take away my mourning and give me music; remove my sackcloth and clothe me with beauty; still my sighs and fill my mouth with song, then give me summer weather as a Christian.

--from The Valley of Vision, Banner of Truth, p. 81

Prayer and Waiting

Prayer and waiting are intrinsically linked, joined at the hip. Prayer makes no sense apart from waiting. Prayer is about being made in the likeness of Christ. Conformed, reformed, transformed. If prayer was only about getting things - getting even, getting rich, getting well, getting justice - then we would call it something else. We have lots of names to describe the quest and method for getting those things: magic, medicine, capitalism, lobbying.

But prayer is not about bartering and bargaining with God, haggling for the best deal: a pound of piety for a remission of sickness. Prayer, at its heart, is about becoming like the crucified and risen Christ. And that is a work like wind carving stone. It is a slow, painful, toiling work, rarely swift or easy. It is riddled with wrenching setbacks, and its breakthroughs are more serendipitous than calculated. There are disciplines for prayer, to be sure, but no mechanisms. Gimmicks and panaceas - like glittery gimcrack lures for fisherman - are widely available and equally useless. There is simply no substitute for becoming like Christ other than being with Christ, and especially with Him in solitude and suffering and sorrow. And so prayer, like fishing, is about waiting. Prayer is the poetry of waiting.

Calvary's Anthem

Heavenly Father,

Heavenly Father,Thou hast led me singing to the cross

where I fling down all my burdens and see them vanish,

where my mountains of guilt are levelled to a plain,

where my sins disappear, though they are the greatest that exist, and are more in number than the grains of fine sand;

For there is power in the blood of Calvary

to destroy sins more than can be counted

even by one from the choir of heaven.

Thou hast given me a hill-side spring

that washes clear and white,

and I go as a sinner to its waters,

bathing without hindrance in its crystal streams.

At the cross there is free forgiveness for poor and meek ones,

and ample blessings that last for ever;

The blood of the Lamb is like a great river of infinite grace

with never any diminishing of its fullness

as thirsty ones without number drink of it.

O Lord, for ever will thy free forgiveness live

that was gained on the mount of blood;

In the midst of a world of pain

it is a subject for praise in every place

a song on earth, an anthem in heaven,

its love and virtue knowing no end.

I have a longing for the world above

where multitudes sing thy great song,

for my soul was never created to love the dust of earth.

Though here my spiritual state is frail and poor,

I shall go on singing Calvary's anthem.

May I always know that a clean heart full of goodness

is more beautiful than the lily,

that only a clean heart can sing by night and by day,

that such a heart is mine when I abide at Calvary.

Calvary's Anthem, from The Valley of Vision: A Collection of Puritan Prayers and Devotions, ed. Arthur Bennett (The Banner of Truth Trust, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1975), p. 173.

More

Why do I trifle with trivialities? Why do I make mud pies in the slum, rather than run on the beach, the shores of Your ocean-like love? Why don't I plunge in?

I remember when You came to me in a dark basement bedroom. I surrendered all and You filled me with joy unspeakable and full of glory. I sang. I danced. I laughed. I cried. You had never been more real to me. I wanted to never lose the sense of Your smile again.

But I did.

And moments like those have been too seldom.

How much have I robbed from my wife, my children, my flock, by not being more with You, having more of You? By You not having more of me? How much more could we all experience of Your grace, Your love? You beckon us to Your table to take our fill of solid joys and lasting treasures. Why do we -- do I -- fritter my energies away on vain pursuits? Why do I spoil my appetite with pleasures that fade so fast?

I want more of You. I'm sorry I've been so slow to believe Your promises. So disinclined to seek Your face. So hard of heart. I've been blind to Your beauty, deaf to Your song, too stuffed with the junk-food of the world to taste and see that You are good. I've tried to slake soul thirst with cisterns, broken, empty, disappointing.

But You are the fountain of living water. You offer a well springing up to eternal life. You beckon me to come, to drink freely, without money, without price.

If I knew You as You really are, I would have asked for more.

I'm asking now.

More, Lord. Give me more.

Devoted to Prayer: Lessons from Andrew Bonar

Regarding his failures, on July 22, 1838, Bonar wrote: "In the morning was specially impressed with the awful fact that by losing one hour of prayer every day by not rising early, I lost twenty days of prayer in the course of a year." On January 3, 1842, he was still lamenting his failures in prayer: "On looking back I am grieved and vexed, most of all at my few hours of real prayer all this year. How little have I done for God in the Spirit." Even fifteen years later, the struggles continued. April 4, 1857: "For nearly ten days past have been much hindered in prayer, and feel my strength weakened thereby."

One gets a flavor of his resolution to grow in prayer, even in the face of his weakness and failure, in the following entry from September 26th of that same year: "I purpose (and yet I cannot effect even this unless I get help from the Lord) to go earlier to bed and rise at six; and spend from six to eight in prayer for myself, my parish, and the cause of God through the world. Oh, if I could do this all the days of my life while I have health, for I have never yet succeeded in such resolutions, and never yet have I given much time to prayer daily."

One gets a flavor of his resolution to grow in prayer, even in the face of his weakness and failure, in the following entry from September 26th of that same year: "I purpose (and yet I cannot effect even this unless I get help from the Lord) to go earlier to bed and rise at six; and spend from six to eight in prayer for myself, my parish, and the cause of God through the world. Oh, if I could do this all the days of my life while I have health, for I have never yet succeeded in such resolutions, and never yet have I given much time to prayer daily."These kinds of confessions are both encouraging and challenging. They are encouraging because I also struggle to keep my resolutions in prayer, and I am heartened that one of these great saints from the past also struggled. It makes me feel that I am not alone. And it gives me hope that I may yet develop a deep and consistent prayer life.

But I am also challenged because Bonar never gave up in his fresh resolutions for prayer. Statements like those above occur again and again, decade after decade, often with reports of significant times spent in prayer. For example, on April 25, 1840, he wrote, "Felt a heart to pray much and earnestly; have felt it easy to pray all day." On August 4, 1842: "Passed six hours today in the church in prayer and Scripture reading, confessing sin, and seeking blessing for myself and the parish." And on September 16, 1851: "In prayer in the woods for some time, having set apart three hours for devotion; felt drawn out much to pray for that peculiar fragrance which believers have about them, who are very much in fellowship with God."

Perhaps most helpful are the strategies that Bonar developed to strengthen his prayer life. For example, he learned:

- To pray while traveling: September 19, 1840: "God has this week been impressing much upon me the way of redeeming time for prayer by learning to pray while walking or going from place to place."

- To give prayer first place every day: September 29, 1848: "By the grace of God and the strength of His Holy Spirit I desire to lay down the rule not to speak to man until I have spoken with God; not to do anything with my hand till I have been upon my knees; not to read letters or papers until I have read something of the Holy Scriptures."

- To take advantage of short but frequent praying: August 25, 1849: "Led to think today that my way of praying is chiefly to be by bolts upward, not by very long prayers at one time."

- To pray every hour of the day: January 3, 1856: "I have been endeavoring to keep up prayer at this season every hour of the day, stopping my occupation, whatever it is, to pray a little, seeking thus to keep my soul within the shadow of the throne of grace and Him that sits thereon."

Are you failing in prayer? Take heart from this great man of God. Resolve afresh to devote yourself to prayer and develop strategies to help you. And remember that learning to pray will be a lifelong journey, just as it was for Andrew Bonar.

Making It Personal

- Can I honestly say that I am devoted to prayer?

- Despite my failures in prayer, is my life marked by consistent desire and renewed resolutions to grow in prayer?

- Have I grown in prayer in the past five years?

- Which of Andrew Bonar's strategies for prayer might be helpful in my prayer life?

NOTE: This article was originally written for Pastor Connect in September 2006.

C. S. Lewis on Prayer

C. S. Lewis

Master, they say that when I seem

To be in speech with you,

Since you make no replies, it’s all a dream

--One talker aping two.

They are half right, but not as they

Imagine; rather, I

Seek in myself the things I meant to say,

And lo! The wells are dry.

Then, seeing me empty, you forsake

The Listener’s role, and through

My dead lips breath and into utterance wake

The thoughts I never knew.

And thus you neither need reply

Nor can; thus, while we seem

Two talking, thou art One forever, and I

No dreamer, but thy dream.

C. S. Lewis, Poems, p. 122-123

Come Messy

Here's a passage about child-likeness and how we must "come messy" when we pray that particularly helped me.

"Jesus wants us to be without pretense when we come to him in prayer. Instead, we often try to be something we aren't. We begin by concentrating on God, but almost immediately our minds wander off in a dozen different directions. The problems of the day push out our well-intentioned resolve to be spiritual. We give ourselves a spiritual kick in the pants and try again, but life crowds out prayer. We know that prayer isn't supposed to be like this, so we give up in despair. We might as well get something done.

What's the problem? We're trying to be spiritual, to get it right. We know we don't need to clean up our act in order to become a Christian, but when it comes to praying, we forget that. We, like adults, try to fix ourselves up. In contrast, Jesus wants us to come to him like little children, just as we are.

Come Messy

The difficulty of coming just as we are is that we are messy. And prayer makes it worse. When we slow down to pray, we are immediately confronted with how unspiritual we are, with how difficult it is to concentrate on God. We don't know how bad we are until we try to be good. Nothing exposes our selfishness and spiritual powerlessness like prayer.

The difficulty of coming just as we are is that we are messy. And prayer makes it worse. When we slow down to pray, we are immediately confronted with how unspiritual we are, with how difficult it is to concentrate on God. We don't know how bad we are until we try to be good. Nothing exposes our selfishness and spiritual powerlessness like prayer. In contrast, little children never get frozen by their selfishness. Like the disciples, they come just as they are, totally self-absorbed. They seldom get it right. As parents or friends, we know all that. In fact, we are delighted (most of the time!) to find out what is on their little hearts. We don't scold them for being self-absorbed or fearful. That is just who they are . . . .

This isn't just a random observation about how parents respond to little children. This is the gospel, the welcoming heart of God. God also cheers when we come to him with our wobbling, unsteady prayers. Jesus does not say, 'Come to me, all you who have learned how to concentrate in prayer, whose minds no longer wander, and I will give you rest.' No, Jesus opens his arms to his needy children and says, 'Come to Me, all who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest' (Matthew 11:28, NASB). The criteria for coming to Jesus is weariness. Come overwhelmed with life. Come with your wandering mind. Come messy . . . .

Don't try to get the prayer right; just tell God where you are and what's on your mind. That's what little children do. They come as they are, runny noses and all. Like the disciples, they just say what is on their minds.

We know that to become a Christian we shouldn't try to fix ourselves up, but when it comes to praying we completely forget that. We'll sing the old gospel hymn, 'Just As I Am,' but when it comes to praying, we don't come just as we are. We try, like adults, to fix ourselves up. Private, personal prayer is one of the last great bastions of legalism. In order to pray like a child, you might need to unlearn the non-personal, nonreal praying that you've been taught." (pp. 50-52)

A Praying Life

The first book I will read this year, reflecting perhaps the deepest need in my personal spiritual life at present, is Paul Miller's A Praying Life: Connecting with God in a Distracting World. Like many Christians, I find keeping a strong prayer life difficult. So, I resonated with these opening lines (from David Powlison's foreword):

The first book I will read this year, reflecting perhaps the deepest need in my personal spiritual life at present, is Paul Miller's A Praying Life: Connecting with God in a Distracting World. Like many Christians, I find keeping a strong prayer life difficult. So, I resonated with these opening lines (from David Powlison's foreword):"It's hard to pray. It's hard enough for many of us to make an honest request to a friend we trust for something we truly need. But when the request gets labeled 'praying' and the friend is termed 'God,' things often get very tangled up. You've heard the contorted syntax, formulaic phrases, meaningless repetition, vague nonrequests, pious tones of voice, and air of confusion. If you talked to your friends and family that way, they'd think you'd lost your mind! But you've probably talked that way to God. You've known people who treat prayer like a rabbit's foot for warding off bad luck and bringing goodies. You've known people who feel guilty because their quantity of prayer fails to meet some presumed standard. Maybe you are one of those people."

I am. So, I'm asking God to help me learn to pray and am hoping this book will be helpful in the process. I read the first two chapters this morning and was not disappointed. This book, so far, is not formulaic. It's real. And I put it down it wanting to read more . . . and wanting to pray more. Which is the whole point.

If God is Sovereign, Why Pray?

There is no theological issue more knotty than the relationship between divine sovereignty and human responsibility. And this is no mere academic question, for our understanding here (or lack thereof) significantly affects such practical areas as evangelism and prayer.

Prompted by an ongoing correspondence regarding predestination and free will, a friend asked me these thought-provoking questions:

- If God already knows what will happen (and what choices will be made, etc.), can He change the outcome?

- What is the purpose of prayer?

- Can our prayers for someone's salvation actually make a difference? In a way, I don't want my salvation to hinge on other people's prayers, yet neither do I want my prayers to accomplish nothing.

What follows is a slightly edited version of my response to my friend.

Your thought-provoking questions cut to the heart of the issue. You find yourself in a theological quandary familiar to many of us. You want prayer to make a difference, yet you don't want such a tremendous matter as your soul's eternal salvation to rest ultimately in the prayers of fallible people. Those two concerns represent the two opposite and extreme positions so many adopt but which we must carefully avoid.

On one side we have the extreme of determinism, or fatalism. This position basically says with Doris Day, "Que será, será; whatever will be, will be." It reasons, "Since God is sovereign and in control, it doesn't matter whether I pray or not. God knows His elect, and He will save them without my help. He will do His will regardless of what I do or fail to do."

On the other side of the issue, there are those who insist that "prayer changes things," and that God is actually limited to our prayers. They believe He either can't or won't work except in response to prayer.

Both of the above positions are partly true. The problem is not in what they affirm but in what they deny.

While it is true that God is sovereign and will accomplish His will, it is not true that I don't need to pray. And while it is true that prayer changes things, it is not true that God is limited by my prayers.

Our tendency is to take only one side of the truth and misuse it. We either sacrifice God's sovereignty on the altar of human responsibility, or vice versa. In either case, our mistake lies in emphasizing a biblical truth without regarding its intended function.

The Scriptures clearly teach that God is sovereign in all things:

- God "works all things after the counsel of His own will" (Eph. 1:11).

- God does His will "among the host of heaven and among the inhabitants of the earth; and none can stay his hand or say to him, 'What have you done?'" (Dan. 4:35).

- "The Lord has established his throne in the heavens, and his kingdom rules over all" (Psa. 103:19).

On the other hand, the Bible also clearly and forcefully affirms man's responsibility. In the realm of prayer, for example, we read that:

- "The prayer of a righteous person has great power as it is working" (James 5:16).

- "You do not have, because you do not ask" (James 4:2).

- "Ask, and it will be given to you; seek, and you will find; knock, and it will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives, and the one who seeks finds, and to the one who knocks it will be opened" (Matt. 7:7-8).

- In nearly every one of his letters, Paul requests prayer and reports of his own intercession for his fellow believers (e.g. Eph. 1:16-23; 3:14-21; 6:18-20).

- Paul prayed for the salvation of his fellow Jews: "Brothers, my heart's desire and prayer to God for them is that they may be saved" (Rom. 10:1).

So how do we fit these two seemingly contradictory sides of Scripture together into one coherent paradigm? We must realize the following three things.

1. God's unchangeable nature does not cancel out His personal interaction with humanity.

God is immutable, or unchangeable. Psalm 102:27 declares of Him, "You are the same, and your years have no end." God Himself says, "I the Lord do not change" (Mal. 3:6). Hebrews13:8 tells us that "Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever."

God knows all things from the beginning (Isa. 46:9-11), and He does not change His eternal will. If He did, His wisdom or knowledge would be deficient. We must not rob God of His omniscience in our attempt to safeguard prayer's effectiveness.

But then you might remember instances in Scripture where God did "change His mind" in response to prayer. For example, after the children of Israel committed idolatry in worshiping the golden calf, God said to Moses, "I have seen this people, and behold, it is a stiff-necked people. Now therefore let me alone, that my wrath may burn hot against them and I may consume them, in order that I may make a great nation of you" (Exo. 32:9-10).

The next three verses record Moses' prayerful response for God to remember His promises to the patriarchs and turn away His anger. Then verse 14 says, "The Lord relented from the disaster that he had spoken of bringing on his people."

Does this mean that God changed His mind about something He had planned to do from eternity? Does this text imply that God is not all-knowing? I don't think so.

The Scriptures often speak of God "regretting" something. For example, 1 Samuel 15:10-11 says, "The word of the Lord came to Samuel: 'I regret that I have made Saul king, for he has turned back from following me and has not performed my commandments.' And Samuel was angry, and he cried to the Lord all night." But in the very same chapter, we also read, "The Glory of Israel will not lie or have regret, for he is not a man, that he should have regret" (v. 29).

So there is a sense in which God does regret and thus change His mind, and there is another sense in which He does not. God doesn't experience regret or change His mind in exactly the same ways we do.

God does not change because of a flaw in His nature. When Scripture says that God regrets something or changes His mind, we must understand those texts to speak of God's moral and personal response to people and events considered in themselves; it is not a response based on some deficiency in His knowledge or a change in His eternal will or purpose. God's unchangeableness does not cancel out His personal interaction with human beings.

2. Prayer is one of God's ordained means of accomplishing His purposes.

The example of Moses given above is a perfect illustration. Consider also Daniel's prayers for the end of Israel's captivity in Babylon.

According to Daniel 9:2, he knew that God had promised release after seventy years, but this didn't keep him from praying! Rather, it motivated him to pray. As Daniel 9:3 says, "Then I turned my face to the Lord God, seeking him by prayer and pleas for mercy with fasting and sackcloth and ashes."

We learn from this that the true function of God's promises is always to motivate us to action, never to lull us into inactivity. God wants us to pray, but not because He can't act without us praying. As John Piper points out, God wants us to pray that He might be glorified (John 14:13) and that we might be satisfied in Him (John 16:24).

3. If we deny God's sovereignty over human choices and events, insisting that God will not infringe upon man's freedom, we actually do more damage to prayer than when we assert God's sovereign freedom.

Why should we ask God to save someone if He has already done all He can or will to save them? Should we not be focused solely on begging the person to comply with God? Or are we to pray things like, "Lord, please help Jim believe the gospel, but don't touch his free will" while Jim's biggest problem is his rebellious will bent on sin?

Denying God's ability or authority to rule over the wills of men does not help prayer. It hinders prayer. Of course, a mystery still remains. We can't fully explain how God's sovereignty interrelates with man's will, but we know that we can't deny either.

So, my friend, if we stick to the Scriptures, it seems that both of your concerns are answered. "Can we pray that someone will be saved and it actually make a difference?" Absolutely. God has commanded us to pray, and He uses our prayers to accomplish His purposes and glorify His name.

"Does this mean that the salvation of someone's soul hinges on my prayers for them?" No. A person's salvation hinges on Christ's death on their behalf and the Holy Spirit's work in applying salvation to their heart.

But neither do my prayers "accomplish nothing." For just as my hand animates and moves the glove I wear, so God animates and moves people to accomplish His purposes. The glove is not determinative; I am. But the glove is involved because it is filled with my hand. My prayers are not determinative; God is. But I am involved if I am filled with God's Spirit.